GABRIELE EVERTZ

“In the Studio with Gabriele Evertz”

Edited Transcript

Produced by American Abstract Artists

Scientists tell you that in nature light makes the color, but a painter will tell you that colors make light.

I was born in 1945 in Rangsdorf, which is a suburb of Berlin. I spent my first seven years there. There were not many children to play with, so I spent my time in the nearby forest or at my grandmother's house.

My grandmother had a collection of oil paintings, amongst which was Monet’s Bouquet of Sunflowers, which impressed me greatly. Imagine my surprise when I saw it at The Met Museum–the original.

Paul Klee said, “I paint in order not to cry.” That's pretty much it. Just imagine a 7-year-old girl walking through all this destruction, playing in the ruins and trying to make sense of this world. I found my own version of beauty around me. As a child in Berlin, I would walk along the curb and look for colored glass. When I found it, I would hold the glass up to the light and just delight in the pure joy of looking at a blue or a green against the sunlight. I think the appreciation, the joy, and the meaning of color has been with me for a long time.

When I came to Berlin, it was pretty much destroyed. It was 1952 and there were these radical shadows– these sharp shadows. I'm beginning to think that that has something to do with wanting to work in hard edge. The area was designated as the American Sector. After I completed an apprenticeship with an architectural firm in Berlin, I made a deal with my parents to go to New York for a year, then come home and get married. Well guess what? Didn't happen. I love to be in this country– this open society versus the closed society that I was living in and experiencing. I was really very curious. With $50 in my pocket, I left Berlin on the 25th of May, 1965.

The apprenticeship with the architectural firm gave me the license to be a draftsman, and that's how I found employment here in New York. Drawing was always very important to me. As a draftsman, I had to draw facades. I drew with ink on mylar, so I had to be very correct and perhaps that explains a little bit about my work method.

I give Hunter College credit. When I enrolled in the MFA, Sandy Wurmfeld and Bob Swain both taught color, but they were opposite directions which immediately pointed to many different approaches to color. They had different philosophies. Hunter College was the only place where you could study color; it was an oasis. I knew that I had to study hard because the history and theory of color was my entry point.

Mac Wells was my first mentor. I TA’ed for his class and he proposed me to the American Abstract Artists in 1996. It was the first time I had an audience and talked about my work, so it was pretty thrilling. When I decided to be a color painter, the first thing I did was study the pedagogical work of Itten, Klee, and Kandinsky. That's where the foundation comes from.

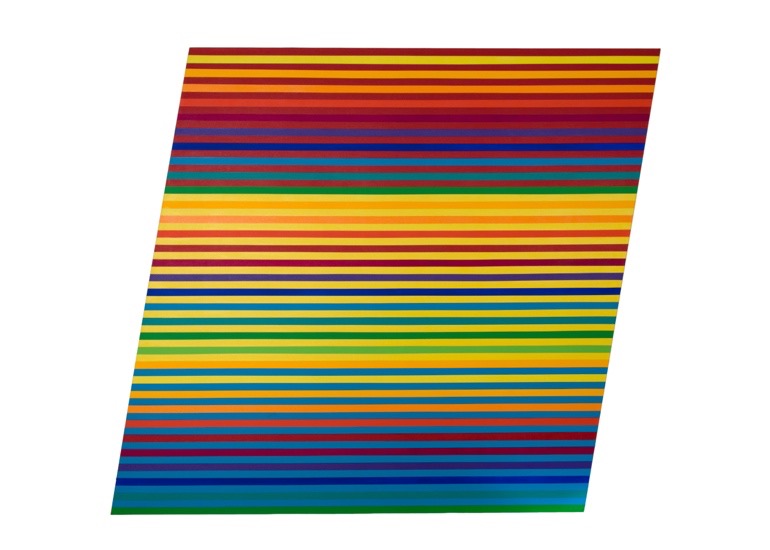

A painter is always a painter– it's just a question of getting a studio and making work. You see the world like a painter; you see it differently. I had to remove considerable obstacles before I could call myself a painter. The subject matter developed over a longer period of time. At that time, I thought my artistic inheritance was expressionism, so the brush stroke was very important. That's what I painted. Pollock was one of my heroes; you don't have a German Pollock. But when I received criticism in school about the work, it was always about me, my brushstroke, what led me to do this and that. I didn't desire that; I wanted people to engage with color and color interaction, so I knew I had to change my form. I had to get rid of all the brush strokes and the marks and make very precise paintings so that the form disappears, and the color comes forward. It wasn't supposed to be about me– it was supposed to be about the life of color, the interaction of color, and sharing with the audience the joy of sight and seeing. I wanted less attention on the shape, and the best thing I could come up with was the line. The line still has two borders where contrasts can occur and light can develop, and no one owns the stripe. If you call it perceptual abstraction, which comes out of William C. Seitz’s show, “The Responsive Eye”– the fact that color is the dominant force is left out of that label. The best I can come up with is that it's a line structure in support of a color concept.

I painted some horizontal paintings, but it took away from what the color does. I just recently showed a horizontal work that I did in 1999. Sure enough, people tend to stop investigating once they think they have the answer, so they were thinking about water, sunset, landscape– and that wasn't it. The diagonal takes you into the space, and I needed that. Although I thought the color would take you into the space, I couldn't just rely on that. I needed some other two-dimensional element that takes you into this space and that was the diagonal.

Beauty can be achieved with intuitive colors, but with structural colors comes exaltation. For me, the beauty is to grasp the power and aliveness of color. That brings me back to your other question about the line; the line is not geometric for me. I saw a visual sign that a Native American language had for beauty, and that’s the line– man walking upright on earth. It's not really abstraction. Abstraction refers to something abstracted from, and I'm not doing that. I'm putting colors together that hopefully interact and have a sense of liveliness that only color and light can give you. I'm not painting with light; I'm painting with colors, and colors make light in the painting.

Early on, I was in my studio wondering, “What should I paint? What should my direction be?” There was a blue 8 1/2 x 11 inch sheet of paper pinned to the studio wall. It looked so beautiful to me– it was ultramarine blue, silkscreened. I looked at it for a long time. When I changed my viewpoint to another spot on the wall, I saw the afterimage, that orange pulsating– light communicating back to me that I was alive. I had a sensation, a very important moment that made me realize, “That's what I want to paint. I want to concentrate on color.” The time was not favorable for color painting; it was the late 1980s.

In the beginning, I had to have all 12 colors in my painting. I couldn't leave one out. The circle is set up in such a way that it shows the relationship. I had to work out my color circle and that's a very difficult thing. Everybody says, “Well yes, the primaries are red, yellow, blue.” But what? Which red, which blue? That takes a while to educate your eye and to find out which one is the right one for you. It took me a long time to let go of the circle, to concentrate on individual colors, to bring the black and white in, to bring the gray in.

The major shift happened when the pandemic hit. I couldn't use these bright, joyful colors anymore. I looked for the prehistoric palette, the earth colors. It connected me to the first artists. This is what you see in Nocturnus. To express strength, to share the strength that color can give to the viewer: that's my new expectation of art.

Some people think they're color painters, but they're really light /dark painters; they're more interested in the value, not in the chromatic aspect of it. What you bring to it determines your particular sensibility. Painting is about, first and foremost, the visual experience before anything else. Color had to be something else for most of the history of color. Just in the 20th century, it took abstraction to free it. That's fantastic because with abstraction, color could be autonomous. Color cannot function when it's small; it's a physical relationship to the work. Painting has to be at least as tall as you are in order to challenge you, and to invite you in, and to ask questions.

In 1998 when I had my first solo show, I was doing the Motion Parallax series. It had to do with moving the sides of the painting by a few degrees, shifting it, because I wanted the viewer to interact with it. Already that little shift, that little change in the physicality of the work changed the attention of the viewer to something else. It already bordered on sculpture, so I knew I had to abandon that.

Kandinsky asked, “What replaces the object in abstraction?” For me, it is science. Science filled that void for me and it gave me certainty. “What is simultaneous contrast? What's an afterimage? What are all these effects, how do they come about, and what is the explanation?” I wanted to know; that doesn't mean the viewer has to know it, but I wanted to understand what causes certain visual excitement. Is it real? Is it repeatable?

Visually, I think the shape comes first when the viewer initially approaches the work. Then, there is confusion because the stripe is not straight. People either figure out how the grouping of the stripes occurs, or they go into the color. Most of them respond, “Well it’s stripes, or not stripes.” By then, the color already takes over. The stripe is recognized at a different level in your mind than the color. Color has a deeper recognition and enters emotion at a deeper level than the stripe does.

My father was dichromatic, which means he couldn't see green. I loved my father tremendously and as a kid I was always wandering around wondering, “What does the world look like without green?” I tried to imagine that. I never said I wanted to be a painter– it was just understood in my family. My father always said, “You like to paint? Paint me a sunset.” I must have painted 100. Every time I showed it to him, “Nope,” that wasn't it.

I realized already, very early on, that there is an emotional association to a memory, to a visual. That's what he wanted me to paint, of course. I could never get there, but I realized from the beginning that painting is not mimicking what you see; it is a state of mind, it's a psychic memory. Secretly, I think there's a sunset here somewhere.

Transcribed from “In the Studio with Gabriele Evertz.” YouTube, uploaded by American Abstract Artists, 1 August 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9QNk9eLZMEA&t=576s.